The UK Tech Triumph: A $1.2 Trillion illusion masking bias and stifling growth

But behind the headline numbers, $1.2 trillion in value, $7 billion raised in just six months, lies a sobering truth: the money is still only reaching the few, not the many.

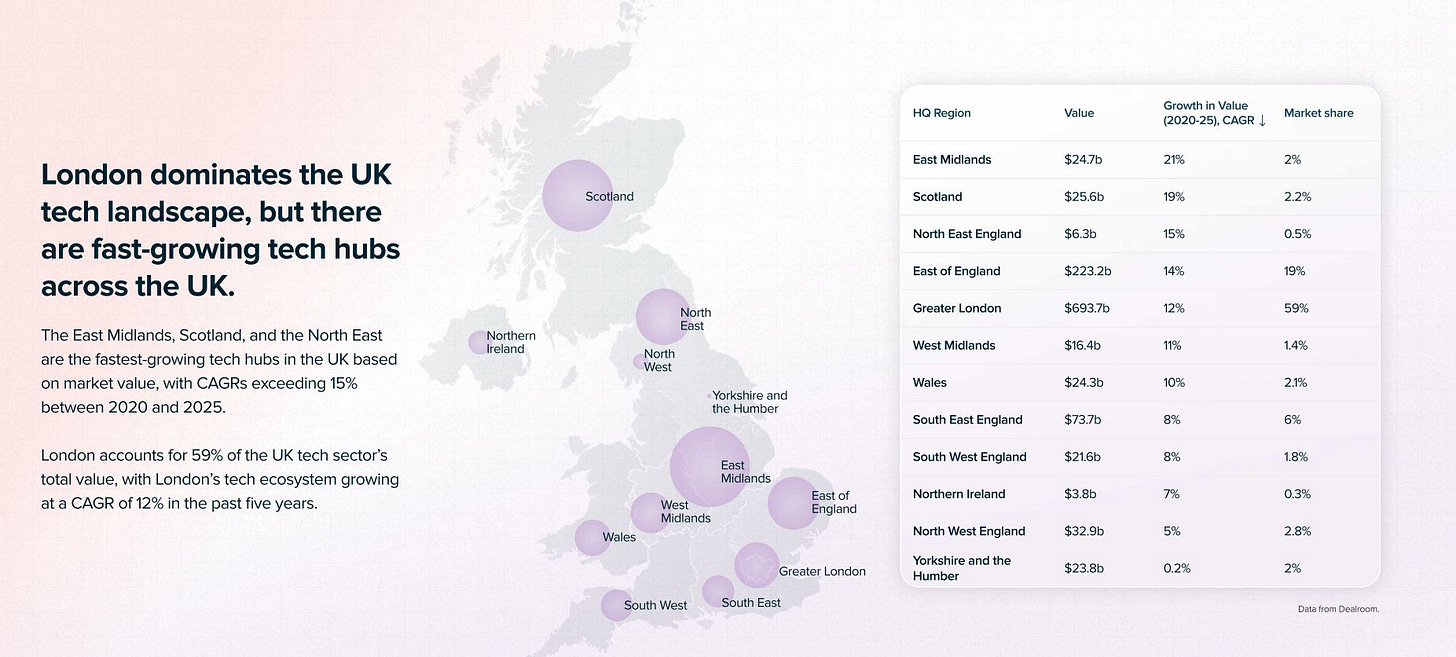

The UK tech scene stands as a beacon of incredible talent, now boasting a combined market value of an astounding $1.2 trillion. This monumental achievement cements its place as the number one tech ecosystem in Europe, with $7 billion invested in start-ups in the first half of 2025, marking the biggest fundraise since 2022, and UK VCs creating 66 new funds in 2024 worth $10.9 billion. London continues to lead, representing 59% of the ecosystem and attracting capital up to seven times more than any other nation or region within the UK. This is, by all accounts, a cause for genuine celebration.

Yet, this success hides a sobering irony: for every £1 invested in female founders, Wales receives just £0.019 and Northern Ireland £0.05, while London absorbs £5.89

Edinburgh, despite being the UK’s second fintech city, secured only £25 million in 2024 less than 0.2% of what London received in fintech funding. Many businesses across the UK struggle for both capital and talent, revealing a gaping disconnect between success stories, systemic support and policy issues.

Is this a symptom of poor investment decisions, a flawed ecosystem, or deeply ingrained biases? The report suggests it's a complex, interwoven tapestry of all three.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Investment Bias and the Female Founder Paradox

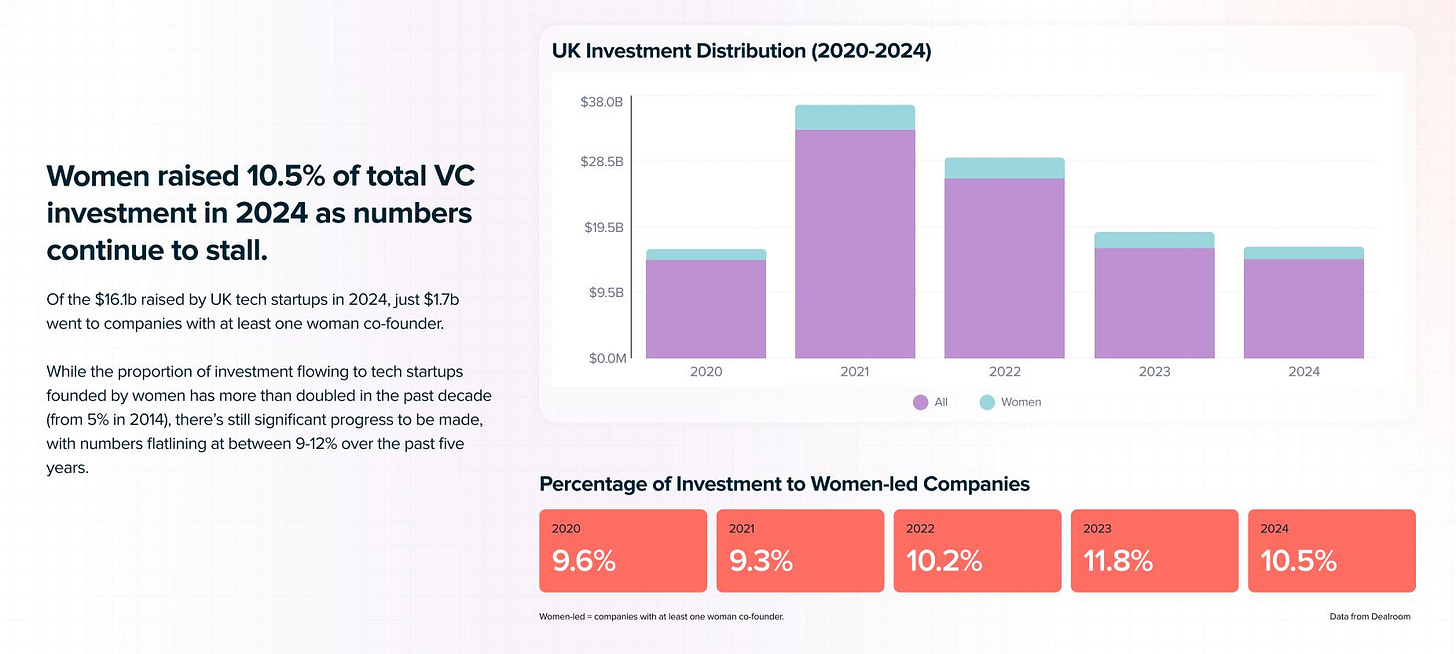

The starkest piece of data revealed in the report is that a systemic bias lies with female founders. Despite their incredible contributions, they are dramatically undervalued, representing a mere 10.5% of the UK VC investment of $16.1 billion raised in 2024 – by a mere $1.7 billion. This is not a new challenge; investment in female led start-ups has been stagnant, stuck between 9-12% over the last five years, despite investment in women innovators nearly doubling from 5% in 2014. This isn't just an equity issue; it's a profound economic drain, costing the UK economy an additional £250 billion.

As Stella Smith of Pirkx states in the report: "The statistics for capital deployed to female-founded firms are getting worse. We need change by writing cheques and levelling the opportunity playing field; unlocking further capital to alternative investments, opening up the public sector to benefit from private sector tech advances, and increasing connectivity and action across diverse sectors to gain accelerated growth for all.”

This national trend finds a powerful, immediate echo in Scotland's VC market. A recent Scottish Enterprise report clearly shows a sharp 57% decline in deals for women-led businesses in Scotland, despite an overall 19% rise in funding for the nation, 2024. While total investment reached a record £704 million, an alarming 3% of that (£22 million) went to women innovators.

The Tech Nation UK report cites £660 million in Scottish VC investment, slightly lower than the Scottish Enterprise report’s £704 million, possibly due to differing methodologies or timeframes. This dramatic imbalance is attributed to growth being "heavily concentrated in a few late-stage mega deals," while early-stage funding, precisely where most women-led start-ups reside, collapsed by 17% to £331 million.

Beyond gender, racial and ethnic minority founders face similar underfunding, with limited data in the report suggesting they receive less than 5% of UK VC capital, compounding the challenges for diverse entrepreneurs.

Beyond Gender: A System Straining Under Its Own Success

The issues extend beyond gender, hinting at broader systemic strains pointing towards geographical imbalances resulting in equity penalties. While London commands 59% of the ecosystem, founders in Northern Ireland and North East England are forced to give up around 25% in equity to secure funding, compared to London companies, which concede only 11.6%.

As a whole, England commands around $14.8 billion in VC investment, an overwhelming 93% of the UK total. Within England, London alone absorbs 67.5%, while regions outside the capital struggle to capture investment: the East of England attracting $1.5 billion, the South East getting $1.4 billion, the Northwest absorbing $597 million, and other regions within England attracting around $500 million.

This leaves disproportionately smaller slices for the rest of the UK's nations: Scotland at $660 million (despite seeing significant overall growth with $25.6 billion in total investment and its VC investment at $660 million, a $120 million increase from the previous year), Northern Ireland at $84 million, and Wales at just $32 million. While these figures reflect existing market size, they also signal how deeply embedded the imbalance has become.

The Tech Nation report makes clear that the issue is not just funding volume, but funding architecture: too centralised, too conservative, and too slow to evolve. The fix, it argues, will not come from optimism alone, but from structural policy change and fast.

Despite the UK housing 23% of European tech firms with more than $500 million in revenue and 38% of growth-stage companies in the $25 million to $100 million range, many struggle to break through the $100 million barrier. The time to get from launch to Series C investment has doubled to 9.6 years since 2019, despite an ostensibly "thriving" ecosystem, hinting at a troubling issue within the investment ecosystem. Alarmingly, 43% of founders are actively looking to move their headquarters out of the UK, driven by concerns over access to growth capital (the biggest barrier for 3 in 4 founders) and availability of top talent (a setback for 1 in 3).

The Tech Nation UK report reveals that investors themselves are facing barriers that impact their ability to support companies seeking to scale. They cite the availability of exit opportunities and institutional capital as key issues. UK IPOs have virtually stalled, with 98% of exits now coming from acquisitions, pushing more tech companies to list overseas. The report suggests that pension fund reforms are needed to enable long-term capital investment into VCs or even Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS) and Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) investment rounds. One in two investors would like to see better tax incentives to increase investment.

The Disconnect: When Reality is Swept Under the Rug

The very report that brings these numbers to light also draws scrutiny. Its foreword, according to analysis, focuses almost exclusively on the positives, praising a "thriving community of more than 17,000 VC-backed start-ups" while seemingly reluctant to acknowledge the cracks hindering this vibrant ecosystem.

This selective narrative, coupled with the absence of explicit efforts to achieve an equal or representative gender spread in its key survey methodology, is starkly highlighted. The survey itself, for instance, disproportionately sampled male founders (68%) compared to female founders (28%), pointing to a persistent gender gap in tech leadership. For a report claiming to understand the "key barriers to growth," failing to ensure diverse voices are heard risks inadvertently perpetuating the very 'disconnect from reality' it implicitly critiques.

More critically, by not adequately amplifying these perspectives, the methodology itself may inadvertently obscure the true depth and severity of the issues faced by underrepresented groups, as exemplified by Scotland's recent figures, suggesting the problem might be even worse than the presented national averages reveal. This oversight risks leading to an incomplete and potentially over-optimistic assessment of the challenges truly hindering this vibrant ecosystem.

The report does lay out several suggestions to help increase investment and fix the stifling ecosystem, but its conclusions feel more focused on encouraging VC investment rather than democratising the ecosystem—despite clear disadvantages for many founders.

Part of the issue stems from the UK's reliance on overseas capital: 66% of VC investment in the first half of 2025 came from international sources, with the US leading the charge, followed by Europe at 14%. Investment from Asian funds fell to 5%, down from 10% the previous year.

The report calls for SEIS/EIS tweaks, like higher thresholds, caters to VCs but lacks the vision to transform the ecosystem. Instead, imagine a teacher in Belfast investing £1,000 in a local female-led start-up, guided by SEIS training. SEIS should be opened to everyday citizens, middle-income individuals, community groups, through free training on platforms like Crowdcube or Innovate UK’s portal. SEIS’s 50% tax relief and loss relief de-risk investments, empowering non-traditional investors to back female founders (10.5% of 2024’s $16.1 billion VC funding) and regions like Northern Ireland ($84 million) and Wales ($32 million). Offering 60% tax relief for investments in underrepresented founders or regions, paired with mentorship, would diversify the investor pool, dismantle VC-centric centralisation, and unlock £250 billion in economic potential.

Government-backed Fund: Over half of growth-stage founders express a desire for a government-backed fund focused exclusively on scaling UK-born businesses, to ensure companies stay headquartered in the UK and are not lost to US exits due to capital flight.

Capital and Talent Reforms: Pension reforms and a government-backed scale-up fund could unlock patient capital and retain UK start-ups, while fast-tracking skilled migration via a Tech Talent Strategy like Canada’s or France’s Tech Visa would address talent shortages (a barrier for 1 in 3 founders).

Regulatory and Procurement Reform: Expand regulatory sandboxes and prioritise underrepresented founders in public procurement to foster innovation.

Enforced Transparency: Mandate gender, race, and regional tracking in investment reporting to ensure accountability.

A Call for Introspection: Poor Investors, Poor Ecosystem, or Deep-Seated Biases?

The picture that emerges is one of a sector achieving headline success but battling a pervasive set of underlying issues. The critical question facing the UK tech scene now is not merely about attracting more capital, but fundamentally addressing how that capital is distributed, who it reaches, and why so many promising ventures still struggle.

Is this simply a case of poor investors, lacking the foresight or courage to back diverse talent and early-stage ventures? Or is it a poor investment ecosystem, with structural bottlenecks like infrastructure, regulation, insufficient institutional capital, and limited exit routes creating systemic disincentives? Or, most uncomfortably, are these symptoms of deep-seated biases – gender, geographical, and perhaps racial and others – unconsciously dictating resource allocation and hindering true, equitable growth?

The evidence strongly suggests it's not a singular problem, but a complex interplay where ingrained biases lead to poor investment decisions, which in turn perpetuate a disconnected ecosystem.

The call for "enforced transparency in investment reporting, including gender, race, and regional tracking" highlights the current lack of visibility into these specific disparities. True innovation is impossible without inclusion. If we don’t fix the flow of capital, we will squander not just £250 billion but our future as a tech superpower. The next unicorn might not be in London. But if we don’t act, we’ll never see it.